This posting focuses on Steps One and Two of an Elaboration Strategy when the Elaboration Task in Step One uses Mnemonics. Mnemonics are contrived procedures for remembering target information. For example, this mnemonic jingle helps in recalling how many days there are in each of the twelve months: Thirty days hath September, April, June and November. All the rest have 31, except February, which has 28. Many primary teachers and parents use the alphabet song to help children recall the names and sequence of letters: you probably still remember it with those catchy lyrics and melody, beginning with: A, B, C, D, E, F, G.... Those are mnemonics because they have been designed to help people retrieve certain information from long-term memory, such as the number of days in each month and the sequenced letters in the alphabet. Mnemonics have been used as elaborators for target information for over 2000 years. Greek orators used mnemonics to recall the vast amounts of information they planned to talk about in the public speeches they had to give without using any written notes to guide them [1]. Mnemonics are effective elaborators of verbal target information for students in school [2], students of all ages, from elementary school [3] to college [4], even elderly adults [5].

The effectiveness of a mnemonic as an elaborator depends in part on the plausibility of the connection between the mnemonic and the target information it is intended to elaborate [6]. For example, the mnemonic sentence, Every good boy does fine, is sometimes used an an elaborator for the notes on the lines in the treble clef of musical notation: E, G, B, D and F. It is effective, in part, because one can conjure up a picture of a boy playing a piano while looking at a page of sheet music. Substituting the word ball for the word boy (i.e., Every good ball does fine.) would likely reduce the effectiveness of the mnemonic because a ball doing fine has nothing to do with musical notation.

Four kinds of mnemonics have been identified as effective elaborators for verbal target information: Keywords, Acronyms, Mnemonic Sentences and Place Method [7].

KEYWORDS

A keyword is a contrived acoustic and visual linkage between separate items of verbal target information, such as words in different languages [8], the names of artists and their paintings [9], and the definitions of words [10]. For example, the keyword lap, along with a visual image of a person holding diamonds in his lap, is an effective elaborator for the target information that a lapidary is a person who cuts stones. Surprisingly, keyword mnemonics are often more effective elaborators in remembering the definitions of words than presenting those words in meaningful sentences [11]. Mnemonic keywords are effective elaborators for all kinds of target information, such as cities and their products [12], states and their capitals [13], famous people and their accomplishments [14], and medical terms and their definitions [15].

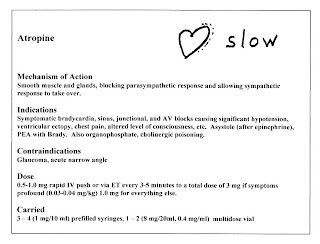

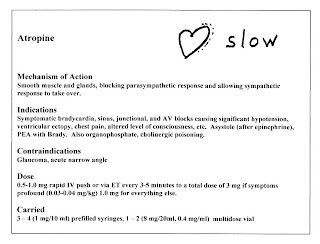

Here is an example of a keyword card created by a paramedic to teach himself the medical terms and critical information about one of the 35 drugs he must know as part of meeting the requirement for an Advanced Life Support Certification. He made similar cards for each of the 35 drugs. The front side of the card has one word: ATROPINE. The back side of the card is shown below. It contains a visual keyword as the elaborator and the target information. The beating heart represents what atropine does, it increases heart rate.

The paramedic student carried out the first step of the Elaboration Strategy by using an Elaboration Task with the information on the back side of the card. He said the elaborator word heart, and that it increases heart rate, along with the target information, over and over, until he could recall them without having to look at the card. Then he began carrying out the second step of the Elaboration Strategy by using a Recall-Practice Task, which consisted of looking at the front side of the card and trying to recite the target information. If he could not recall all the target information then he provided Recall-Practice Guidance by trying to recall the elaborator and the target information connected to it. If that was still not enough, he looked again at the back side of the card and repeated the information a few times. He then moved back to the front side of the card and tried again to recall the target information. This back and forth process continued until he was able to recite the information correctly. Then he began with another drug. Periodically he practiced retrieving the information for drugs he had studied earlier. Eventually he could retrieve the target information for all the 35 drugs.

ACRONYM

When used in instruction, acronyms are mnemonic words formed from the first letter or letters of several words [16]. For example, the first letters of the five great lakes can be combined to form the mnemonic acronym HOMES: Huron, Ontario, Michigan, Erie and Superior. Surveys among college students have found that mnemonic acronyms are well known and widely used [17]. In the first step of instruction, students practice repeating over and over the elaborating acronym, such as, HOMES, and the target information, such as the names of the five great lakes. When they remember that information, they practice recalling just the names of the lakes, using the acronym when they cannot remember.

MNEMONIC SENTENCE

A mnemonic sentence is an expanded acronym, where the target information is associated with a contrived sentence. Mnemonic sentences are effective elaborators with students of different ages [18]. There is some evidence that mnemonic sentences generated by students are more effective elaborators then mnemonic sentences generated by the teacher [19].

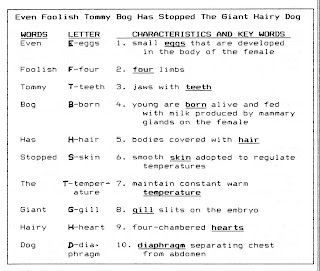

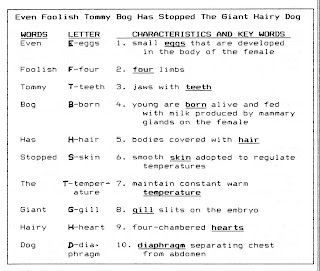

Here is an example of how a teacher might carry out at Elaboration Strategy that is intended to teach the ten characteristics of mammals. The teacher begins with an Elaboration Task and projects a chart onto a screen, shown below, that contains elaboration information and target information.

The elaboration information consists of (a) the mnemonic sentence shown across the top of the chart, (b) the words in the sentence arranged with the characteristics, under the column entitled, Words, and (c) the first letter of each word with its counterpart word in the target information, under the column entitled, Letter. The characteristics are the target information. The teacher points out and reads the sentence at the top of the chart and students copy the sentence. The teacher might also have students draw a picture for the sentence and place it beside the sentence. The teacher explains that the silly sentence will help them remember the ten characteristics of mammals. After explaining how the chart words, the teacher has students copy the information on the chart on one page in their science notebooks. Students could work on memorizing the elaboration and target information by themselves or in tutorial pairs. After a while the teacher begins the second step of an Elaboration Strategy with a Recall-Practice Task. The teacher has students form tutorial pairs and practice asking each other to name the ten characteristics of mammals. When students are unable to recall the characteristics they look back at their copy of the chart. They continue practicing for short periods of time over a number of days, until they are able to correctly retrieve the the characteristics from long-term memory without looking at the mnemonic.

PLACE METHOD

A place method (sometimes called a loci method) utilizes what appears to be a natural cognitive tendency to generate connections between and among encoded verbal information and encoded visual information of the spatial arrangements of that verbal information. [20]. For example, when a five-year-old girl was asked on a number of occasions to recall the names of the 23 students in her classroom, she consistently recalled them in the order of their seating arrangement in the classroom [21]. The place method is most effective as an elaborator when it utilizes students' mental pictures of familiar places, such as their own homes. They mentally assign portions of the verbal target information they are learning to different parts of a familiar place. For example, in learning the names and major characteristics of the planets in the solar system, students might imagine that each planet is located in a different room in their house. They then cue retrieval of those names and characteristics from long-term memory by mentally walking through each room and recalling its imaginary contents. Students using the place method are able to memorize tremendous amounts of verbal target information accurately and quickly [22]. And like most elaborators, mnemonic and otherwise, places generated by students are usually more effective elaborators than places generated by the teacher.

An Elaboration Task utilizing the place method might consist of a piece of paper containing a large floor plan of each student's home or apartment house. They then practice walking through the house and reciting the target information in each room. Eventually, as a Recall-Practice Task, they place the plan out of their view and try reciting the information in each room. When they have difficulty provide guidance having them take the plan out and reciting the information again. They then put the plan away and try to recall the information again. They continue practicing until they are able to retrieve the target information correctly. They continue practicing over a period of days.

_________________________

1. Yates, F.A. (1966). The art of memory. London: Routledge.

2. McDaniel, M.A., & Presssley, M. (1987). (Eds.). Imagery and related mnemonic processes: Theories, individual differences and applications. New York: Springer-Verlag.

3. Kulhavy, R.W., Canady, J.O., Haynes, C.R. & Shaller, D.L. (1977). Mnemonic transformations and verbal coding processes in children. Journal of General Psychology, 96, 209-215.

4. (For example). Borges, M.A., Arnold, R.C., & McClure, V.L. (1976). Effect of mnemonic encoding techniques on immediate and delayed serial recall. Psychological Reports, 38, 915-921.

5. Tchabo, E.A., Hausman, C.F., & Arenberg, D. (1976). A classical mnemonic for older learners: A trip that works. Educational Gerontology, 1, 215-226.

6. Kroll, N.E.A., Schepeler, E.M., & Anglin, K.T. (1986). Bizarre imagery: The misrepresented mnemonic. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory and Cognition, 12, 42-53.

7. Snowman, J. (1989). Learning tactics and strategies. In G.D. Phye & T. Andre (Eds.), Cognitive classroom learning. New York: Academic Press.

8. Atkinson, R.C., & Raugh, M.R. (1975). An application of the mnemonic keyword method to the acquisition of a Russian vocabulary. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning and Memory, 7, 126-133.

9. (For example). Franke, T.M., Levin, J.R., & Carney, R.N. (1991). Mnemonic artwork-learning strategies: Helping students remember more than "Who painted what? Contemporary Educational Psychology, 16, 375-390.

10.Sweeney, C.A., & Bellezza, F.S. (1982). Use of keyword mnemonic in learning English vocabulary. Human Learning, 1, 155-164.

11. (For example). Pressley, M., Levin, J.R., & Miller, G.E. (1982) The keyword method compared to alternative vocabulary-learning strategies. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 7, 50-60.

12. Pressley, M., & Dennis-Rounds, J. (1980). Transfer of a mnemonic keyword strategy at two age levels. Journal of Educational Psychology, 72, 575-582.

13. Levin, J.R., Shriberg, L.K., Miller, G.E., McCormick, C.B., & Levin, B.B. (1980). The keyword method in the classroom: How to remember states anad their capitals. Elementary School Journal, 80, 185-191.

14. Shriberg, L.K., Levin, J.R., McCormick, C.B., & Pressley, M. (1982). Learning about "famous" people via the keyword method. Journal of Educational Psychology, 74, 238-247.

15. Jones, B.F., & Hall, J.W. (1982). School applications of the mnemonic keyword method as a study strategy by eighth graders. Journal of Educational Psychology, 74, 230-237.

16. Bellezza, F.S. (1981). Mnemonic devices: Classification, characteristics and criteria. Review of Educational Research, 51, 247-275.

17. Blick, K.A., & Waite, C.J. (1971). A study of mnemonic techniques used by college students in free recall learning. Psychological Reports, 29, 76-78.

18. (For example). Lowery, D.H. (1974). The effects of mnemonic learning strategies on transfer, interference, and 48-hour retention. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 103, 16-30.

19. (For example). Rohwer, Jr., W.D. (1973). Elaboration and learning in childhood and adolescence. In H.W. Reese (Ed.), Advances in child development and behavior (Vol. 8, pp. 1-57). New ;York: Academic Press.

20. Bellezza, F.S. (1983). The spatial-arrangement mnemonic. Journal of Educational Psychology, 75, 830-837.

21. Chi, M.T.H. (1985). Interactive roles of knowledge and strategies in the development of organized sorting and recall. In S.F. Chipman, J.W. Segal, & R. Glaser (Eds.), Thinking and learning skills (Vol. 2, pp. 457-484). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

22. Kulhavy, R.W., Schwartz, N.H., & Peterson, S. (1986). Working memory: The encoding process. In G.D. Phye & T. Andre (Eds)., Cognitive classroom learning (pp. 115-140). New York: Academic Press.

23. Brown, A.L. (1973). Mnemonic elaboration and recency judgments in children. Cognitive Psychology, 5, 233-248.

24. Weinstein, C.E., Cubberly, W.E., Wilcker, F.W., Underwood, V.L., Roney, L.K., & Duty, D.C. (1981). Training versus instruction in the acquisition of cognitive learning strategies. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 6, 159-1660

25. Montague, W.E., & Carter, J. (1974), April). The loci mnemonic technique in learning and memory. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Chicago.